Targets for carbon neutrality set by many of the UK’s local authorities are rightly ambitious. But lacking both power and financial resource means that they need some clever tricks up their sleeves. Charlie McNelly, Floriane Ortega and Hannah Yu Pearson explain how the Planning Under Emergency Project might help

If you felt feel that last January was warmer than usual, you were right. In fact, it was Earth’s hottest January in 141 years of record-keeping. It is a similar story with flooding. Of the Environmental Agency’s 400 river gauges, around 25% have smashed an all-time record in the last decade.

With a visible growth in the frequency and intensity of climate-related events, from the Australian wildfires to the widespread flooding in the North of England, there has been a groundswell of environmental concern and calls for action to address climate change. As a part of this growing momentum globally, the UK public sector has been swept by a wave of climate motions and declarations, with 287 of the UK’s 408 principal local authorities declaring climate emergencies.

Of these, many have committed to achieving carbon neutrality in their local area by 2030, following the target set by Bristol City Council, which was the first council in the UK to declare a climate emergency. This 2030 target is 20 years ahead of the British Government’s own 2050 target, illustrating a trend among local authorities to take the lead in limiting the devastating impacts of climate change.

However, within these declarations there is a fundamental tension – firstly, that local authorities do not currently have the planning powers to deliver on the scale of their ambitions; and secondly, that following a long period of austerity and budget cuts, many are still facing considerable financial constraints. This has created a struggle to know what is possible to achieve under existing powers as well as challenges to understand which interventions are the ‘right’ or the ‘best’ ones, and then to be confident enough to commit the large capital sums required.

The ‘Planning Under Emergency’ project has sought to create a practical bridge over this knowledge gap, identifying ‘best in class’ examples of climate interventions from a variety of local authorities across the UK, and aims to present a menu of possible interventions for local government that can make real progress now, without the need to rely on longer term legislative or budgetary changes. The case studies are organised across three themes: planning/green infrastructure, governance and finance/procurement.

Where we believe our project really sets itself apart is in how these case studies will feed into the final project output. In partnership with Commonplace — one of the UK’s leading digital engagement and consultation platforms — we are building an online interactive map of the UK, onto which each case study will be plotted. This will then be made publicly available for anyone interested in plotting a case study of a best practice climate intervention they have led or heard about, thereby helping to bring the case studies to life, contributing to a knowledge base that local government can tap into.

Planning

So how can a climate emergency response be tackled in a plan-led system where producing a local plan takes five years and decisions are bounced back between different planning officers, inspectors and planning committees?

First, addressing the climate emergency doesn’t mean that every decision needs to be rushed. Planning has the right timespan to deal with impacts such as sea-level rise for which well-designed and incremental solutions are often required.

Second, local planning authorities are very well placed to encourage coordinated local climate action as they have responsibility across multiple key sectors (i.e transport, housing, energy, waste) that can directly help to secure progress on meeting the UK’s emission reduction target and even go beyond it.

Third, planning can directly create solutions to one of the key barriers to implement climate action: funding. Councils can, for example, require developers to pay into a ‘carbon offset fund’ for the carbon emissions of all new homes built. For example, Milton Keynes Council’s carbon offset fund has generated more than £1 million for carbon-saving projects, although the Future Homes Standard may hamper this possibility.

Governance

Dedicated, inclusive and innovative decision-making on climate action is taking multiple forms. The most recognisable form of action is the rise of Citizen Assemblies.

Whilst the UK government has created a Citizen Assembly on the climate emergency, this has followed many local authorities that had already taken the lead. The London Borough of Camden, Bristol City Council and Oxford City Council all held Citizen Assemblies to agree on proposals on housing, transport, green spaces and waste, to name but a few topics. A Citizen Assembly differs from most other forms of community engagement organised by councils because it goes beyond consultation; it is a representative selection of the population, pays the citizens for their time, and comes to decisions that are fed directly into councils’ action plans.

With a typical Citizen Assembly costing a local authority upwards of £75,000, what then for those authorities less able to afford this form of inclusive engagement? Local authorities with the greatest budget cuts and with the most vulnerable and marginalised populations are also likely to be those most disproportionately affected by changes to the climate, and consequently those most in need of more rigorously inclusive climate action plans that deliver across health, housing, transport etc. The need for exploration of how to finance and organise for inclusive action is more pressing than ever.

Finance

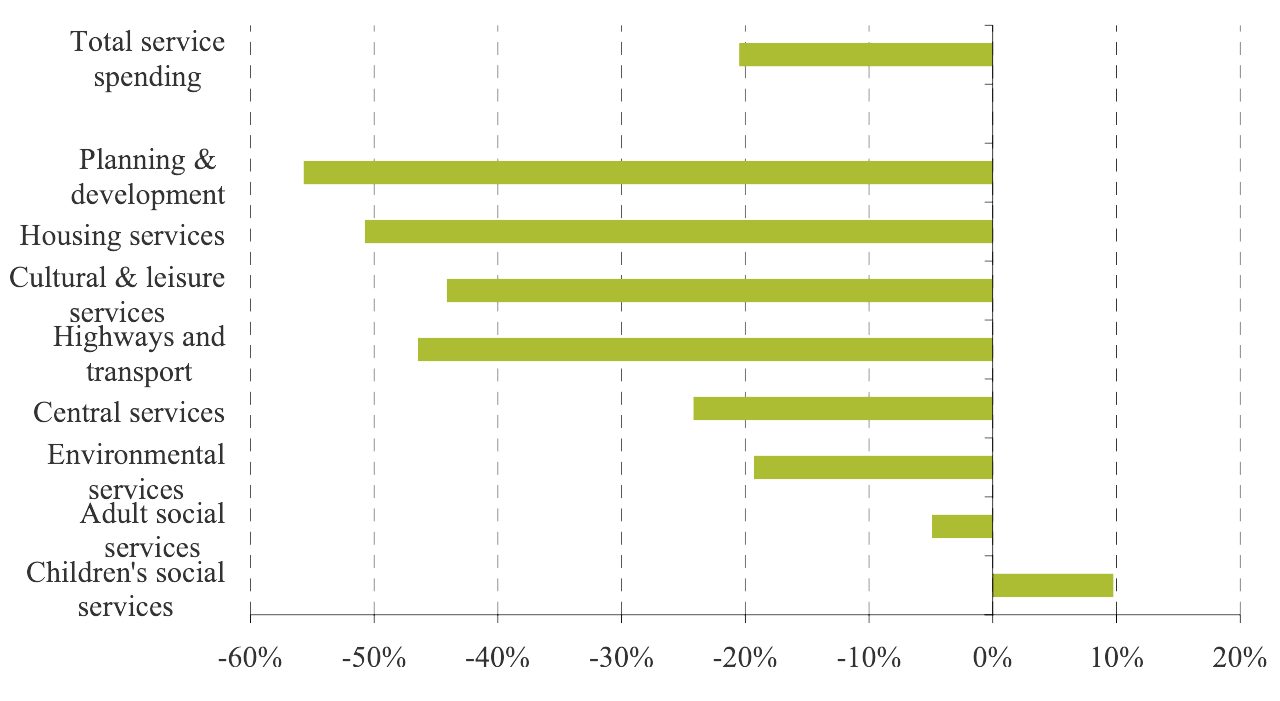

‘And how are you going to pay for that?’ is one of the enduring comments, critiques and responses to climate action. Although often used for negative rhetorical purposes, when positioned in recent British history, it does ring somewhat true. It is hard to overstate the impact of the policy of austerity and public sector budget cuts on local government’s ability to identify, develop and invest in projects. Between 2010/11 and 2017/18 spending by UK local government fell dramatically, down 40% in highways and transport, 20% in environment and 55% in planning.

With the turn of the decade and despite the ‘end of austerity’ being declared, little has changed on the ground. The improvement of local authorities’ financial situation is at best proceeding at a crawl, and reserves continue to be used to plug core funding gaps, diverting funds away from one of its key purposes: delivering projects. That being said, a few councils have given cause for hope by approving dedicated climate emergency budgets: £2 million in Southwark and Birmingham City, and £19 million in Oxford.

Although traditional sources of local government financing, such as the Public Works Loans Board, continue to be very financially attractive, they often require large-scale and don’t necessarily leverage the multifaceted roles councils can play in their area. Alternative approaches that leverage public funds to bring in external investment, improving value for money and sharing risk, can provide greater flexibility, and can bring co-benefits such as engaging the wider community, building awareness, and showing leadership.

Greater Manchester Combined Authority’s EU-funded IGNITION project is working to identify and pilot these smart financing approaches, with a focus on spreading knowledge across wider local government. One particular approach is a novel business model for sustainable drainage. As non-domestic sites are charged for wastewater according to their area of hard surface, this presents an opportunity to introduce Sustainable Drainage Infrastructure (SuDS), which would result in reducing waste water bills for the property enough to offset the initial investment. This was trialled at a primary school in Sale, where five small rain gardens were installed to reduce hard surface by 497 square metres, resulting in an almost 50% reduction in bills.

There is also another way for local government to ‘invest’ in climate action and drive change, through procurement. For context: the latest statistics available put the 2014/15 total procurement spend at £61 billion — about the same as the estimated GDP of Slovenia or Bahrain in 2019, or just over a quarter of the market value of Apple. This is a little outdated, but it is unlikely the figure has changed dramatically.

Procurement has the benefit of being money that was ‘already being spent’, but could be spent in a way that also improves sustainability. Lambeth Council’s Responsible Procurement guide shows how this could be done — for example, by requiring contractors to declare the number of low or zero emissions vehicles that will be included in delivering the work.

As we move to plotting our ‘best in class’ case studies onto the interactive online map, we look forward to sharing this publicly and hopefully seeing others interested in this research plotting their own projects. Watch our Common Place website for the Planning Under Emergency map’s launch!

The Planning Under Emergency team consists of Floriane Ortega, Hannah Yu Pearson and Charlie McNelly. Floriane has been examining how planning could help to deliver the Climate Emergency Ambitions; Hannah investigated into the new governance forms which arose since the beginning of the movement, whilst Charlie has researched on how these climate emergency actions could be financed. George Bright provided editorial guidance for the article