Lorenza Casini AoU and Helen Grimshaw explain how urban designers can best respond to the climate emergency

Last year saw climate emergencies declared across the world, with school strikes and other global movements building momentum. Around 1,400 local authorities in 28 countries across the globe had declared a climate Emergency. In the UK alone, 65% of district, county, unitary & metropolitan councils have now made their own declarations. Many urban areas are now asking how best to respond.

Asking ourselves this very question – how to design sustainably in the context of climate change – is not new to us at URBED. From our beginnings in the 1970s, exploring social and economic sustainability, we quickly progressed into researching and evaluating approaches to sustainable design. Believing cities to be inherently sustainable in their form, URBED spearheaded a new urban approach in the 1990s in which we looked at the type of housing required for the coming century.

We devised the four ‘C’s; Choice, Conservation, Community and Cost, as a structure for looking at the influences on new housing and suggested an innovative model urban form – the sustainable urban neighbourhood. This work was expanded in the late 1990s through research for the British government, the EU, Friends of the Earth and the Housing Corporation. Since then, we have developed urban design, architecture and retrofit approaches that seek to embed key sustainability principles.

Like many practices, we are exploring what this all means for our work; here we consider some of the key ‘ingredients’ that might enable us to respond successfully and meaningfully to the climate emergency we all face.

A holistic approach

Our failure to forge a pathway to lower emissions means we are facing a warming world; that is certain. Substantial reductions in emissions are required to limit this warming as much as possible.

At an urban scale, this means an increasing focus on embodied carbon, which becomes a bigger ‘piece of the pie’ as we get better at delivering uses with low operational (in-use) energy. Part and parcel of this is circularity: a shift from thinking about resource use in linear terms (from extraction, production and use, to disposal) to a more circular approach (that creates and maintains value for as long as possible). These are concepts that pose a learning curve for our sector, but one that we must be willing to put the thought into ‘up-front,’ before key decisions are made.

There is some incredibly valuable work being developed on this front by groups such as LETI (see their Climate Emergency Design Guide and Embodied Carbon Primer), and the Mayor of London’s Good Growth by Design Programme (see Design for a Circular Economy).

But as urbanists we must not become fixated on carbon and frame the whole climate emergency in those terms. Resilience and adaptation are important concepts that we can influence through:

- How we create space for communities to respond positively when climatic or other shocks hit;

- How they can take ownership of these spaces and shape them over time to meet their needs;

- Making spaces work harder, delivering multiple benefits such as green infrastructure that can function as shading, deliver cooling benefits, manage water flows, improve biodiversity and provide a connection to nature that fosters wellbeing. A raft of resources are available to design teams to help with this, including increasingly holistic tools such as Building with Nature.

Robust yet adaptable frameworks

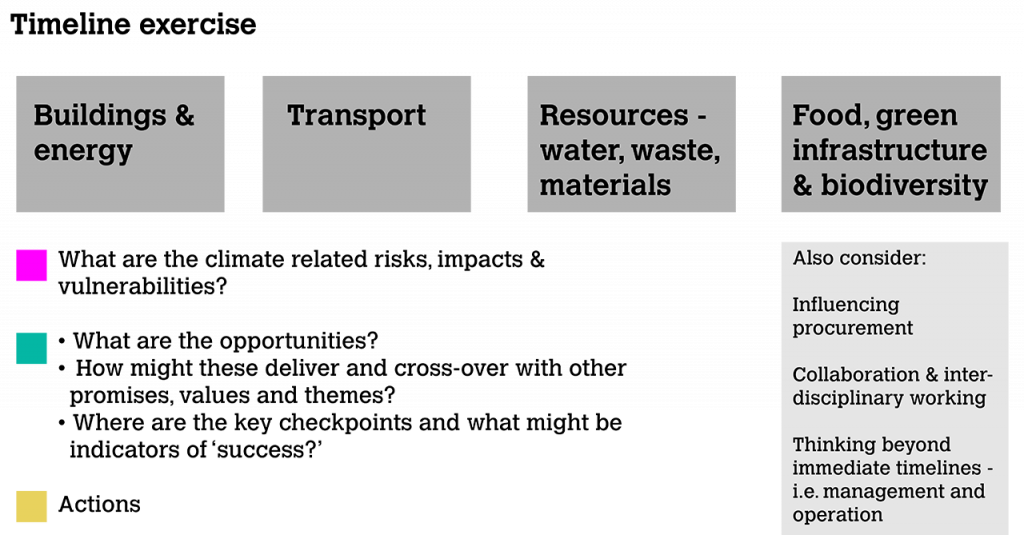

In recent months, we have been exploring with our clients what the climate emergency means for projects over their lifespan. This has included mapping out key impacts, opportunities and actions over a timeline (going as far as 2100). This has proved an effective tool in:

- Helping teams realise how much they can influence, even at the earliest of design stages;

- ‘Joining the dots’ between other aspirations, with the climate emergency seen as an overarching priority that everything is linked to, rather than one component of a wider strategy;

- Beginning to embed circular concepts and thinking about the flexibility of spaces and buildings as needs change.

There is a delicate balance to be struck in setting design frameworks and delivery strategies. The urgency of the climate emergency calls for bold and ambitious responses, but these also need to be agile to account for uncertainty in how impacts will manifest themselves, and other external drivers. Across our work we are looking at how we can:

- Articulate overarching objectives and targets that in some cases are quantifiable, such as the Energy Use Intensity metrics for buildings outlined by LETI, and in other cases are more qualitative in nature;

- Explore different pathways to meeting these objectives. This is particularly important considering the scale and phasing of some masterplans and the number of delivery partners;

- Decide what are mandatory elements of the process — for example, assessing overheating risk;

- Provide checkpoints for each stage in the development process (from masterplanning through to occupancy), with a clear steer on roles and responsibilities.

igloo Regeneration, with which we worked to develop its footprint® sustainable investment policy many years ago, is an example of an organisation that is embedding these issues deeply in their approach to development. In using footprint® as a process, they will be well placed to understand the additional value that its projects deliver for ‘people, place and planet,’ but also to embed this thinking across its design teams and stakeholders, rather than viewing sustainability as an ‘add-on’ or ‘nice to have.’

The climate transition must also be just and equitable

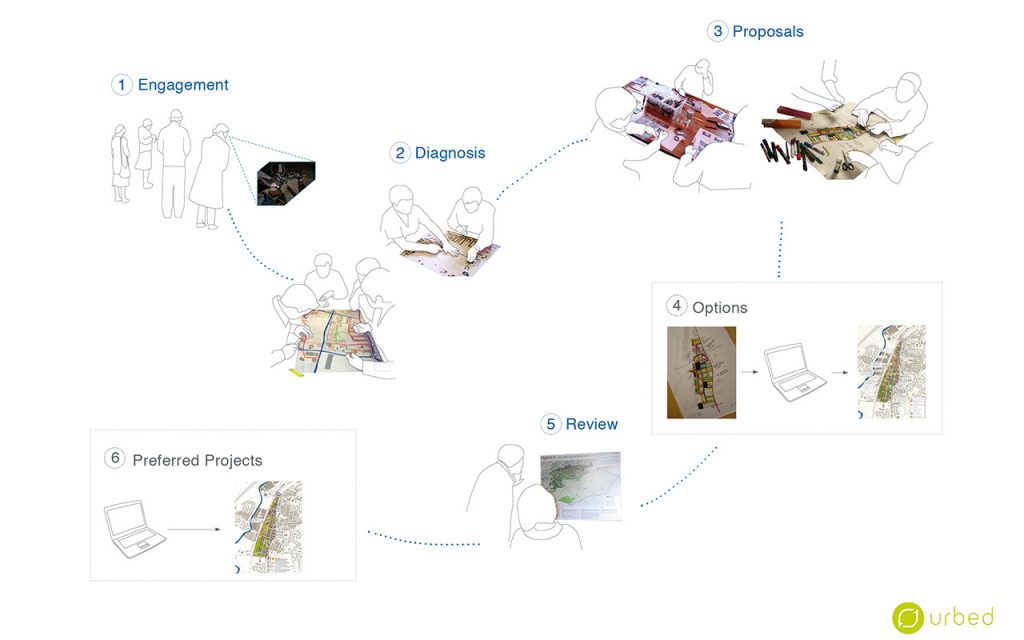

URBED’s Manchester office grew out of the tenants’ movement in Hulme in the 90s. The techniques we developed then, and subsequently with the Glass House, to involve local people in the planning of their own place remain central to our work today. The climate emergency is more of an incentive than ever to involve people in decisions about place. When an open and collaborative relationship between technical experts (us, the designers) and local experts (the communities) can be established at the beginning, this can create long-lasting benefits as well as building resilience in the communities themselves.

In the past, we have done this at Brentford Lock West, London. Working with the client (ISIS Waterside Regeneration) and our fellow designers Tovatt Architects + Planners and masterplanner Klas Tham, we were able to apply our ‘Design for Change’ process to secure a shared vision for the site with the community. Many key components of sustainable design were enshrined in that project – medium to high-density development, permeability and connectivity with an emphasis on walkable neighbourhoods. Although yet to be completed, it is already proving to be a vibrant and diverse neighbourhood.

We continue to apply the principles of participation to our work with communities now, such as Homebaked Community Land Trust and Squash in Liverpool, who are developing long-term plans for their neighbourhoods through high-quality retrofit of existing buildings and food respectively.

We must be willing to challenge our assumptions

We are keen to explore how post-occupancy evaluation might be developed to capture how wider urban strategies help or hinder climate objectives. For example:

- What routes do people actually use and why? Do extreme weather events change how spaces are used and in what ways? Do these findings challenge our assumptions about street layout and the design of spaces?

- Do landscape features, once matured, help or hinder passive design strategies employed at a building level?

We should all be starting to ‘join the dots’ between the various components and stages of development and asking whether what we do works in practice, and if not, how can we make this more climate responsive in future.

All of the ‘ingredients’ we’ve discussed in this article are relevant to the many existing parts of our cities – they relate to the redevelopment of brownfield infill sites, to the retrofit of existing neighbourhoods, to new-build projects and to large scale urban extensions. What is certain is that a culture of shared learning can equip us — urbanists and designers — to support cities, towns and rural areas to respond positively and effectively to the climate emergency we face. We would love to hear from other practitioners about what they are doing to embed this important issue in their everyday work.

Helen Grimshaw is a senior sustainability consultant and Lorenza Casini AoU is associate principal at URBED (Urbanism, Environment and Design) Ltd. URBED is a limited company run by its employees according to co-operative rules